Turkey tail. Lion’s mane. Veiled lady. Long-necked stinkhorn. Their names read like characters in a fantasy tale, but what they really have in common is that they are all used in traditional medicine to cure a spectrum of human ailments. For thousands of years, people around the world have turned to Basidiomycota — the type of fungus we typically think of when we think “mushroom” or “toadstool” — to relieve infections, lower blood pressure, even cure cancer.

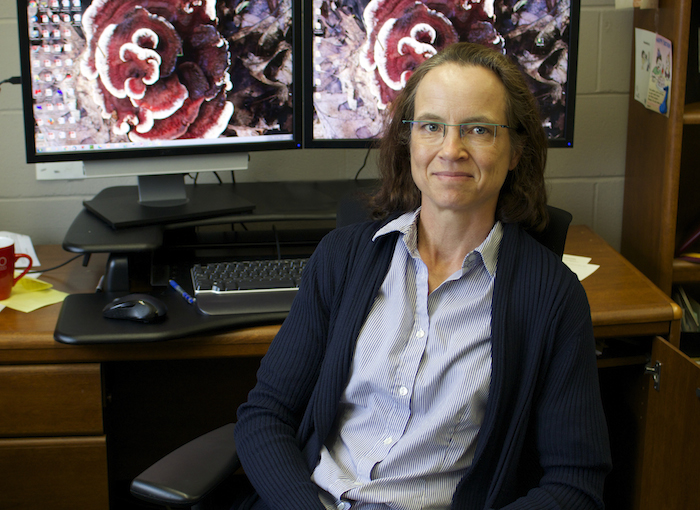

Claudia Schmidt-Dannert, a Distinguished McKnight Professor in the Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Biophysics, is looking to tap these talents by testing various fungi to see if they contain compounds that exhibit medicinal properties. Those that do will become the stars of studies aimed at creating new antibiotic or antifungal drugs to supplement current ones that are becoming less effective as pathogens evolve resistance.

Schmidt-Dannert has already sequenced the genome of the jack-o-lantern mushroom, which is known to produce anticancer compounds. Building on the knowledge gained from that research, last fall she gathered nearly two dozen other types of mushrooms from her neighborhood to grow in culture, then test for pharmaceutical properties.

Preliminary analyses of compounds extracted from these samples in Christine Salomon’s laboratory at the University’s Center for Drug Design have already had a couple of promising “hits.” Eventually, if a particular fungus appears promising enough, she’ll sequence its genome as well so she can pinpoint the specific genes it uses to construct the pharmaceutically active compounds — with the ultimate goal of inserting the genes into bacteria that can then mass produce the useful substances.

“Hopefully we find some very valuable drugs, like antifungal compounds, and hopefully we bring them a little more into the mainstream,” she says.

Mushrooms first caught Schmidt-Dannert’s eye as a potential source of healing substances because their use in traditional medicine suggested they contain compounds that deter bacteria, microscopic fungi, and other things that harm us. In the wild “these type of fungi have to defend [themselves] against grazing insects, invertebrates,” Schmidt-Dannert says. “So the hypothesis is that they must make compounds that fend off other higher organisms.”

Few if any other labs in the world are pursuing this line of research, Schmidt-Dannert says. She feels fortunate to be at the University of Minnesota, where cluster hires have created a core of fungus-focused scientists who can share their work and insights. Some, like Peter Kennedy, have collections of mushrooms from around the world that she can tap. And a weekly Mycology Network study group led by Kathryn Bushley brings together ecologists, biomedical researchers, plant pathologists, microbiologists and others from across the University to talk fungi — each bringing his or her unique perspective to the table.

Schmidt-Dannert is unlikely to run out of research material anytime soon in her quest to turn the wisdom of the past into the cures of the future. Some 30,000 species of mushrooms have already been described, and scientists estimate there could be 15 times that many that we don’t even know about.

“There’s a lot of secrets we haven’t discovered yet,” she says.