"Lions are in such trouble that their conservation is more urgent than extending my research another few years."

You were banned from Tanzania for speaking out about corruption. As a researcher interested in retaining access to your research sites, what tipped the balance for you?

I started out trying to answer basic questions about lions: Why are they social? Why do they have manes? What regulates their populations? But I became increasingly concerned about the effects that human pressures were having on their conservation: unvaccinated domesticated dogs were spreading distemper into the Serengeti, local people were killing lions in retaliation for eating livestock and loved ones, and trophy hunters were over-harvesting lions in the game reserves. We could work with veterinary agencies to vaccinate dogs and local people to reduce conflicts with rogue lions, but the hunting companies controlled most of the lion habitat and they were failing to conserve the lions. Their failure largely stemmed from the corruption in the system. I tried to reform the Tanzanian hunting industry, but the forces of corruption were too powerful to defeat. I knew I was risking my research activities, but I felt compelled to try to make a difference. Lions are in such trouble that their conservation is more urgent than extending my research another few years.

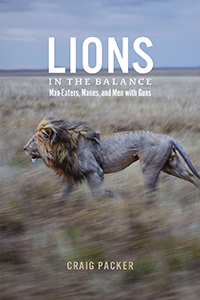

What do you hope people take away from reading Lions in the Balance?

Science is a trip - in all senses of the word. I love doing research. It's the most exciting job in the world, and sometimes it's even important. However, conservation is hard. Saving a species like the lion is incredibly complicated. And it is also a process. You do what you can, and you try to move things forward. It may seem hopeless, but we are not descended from quitters. Keep moving.

Related content

- This Lion Expert Was Banned From Tanzania for Exposing Corruption (National Geographic)

- Craig Packer chronicles lion conservation in new book (AAAS podcast)