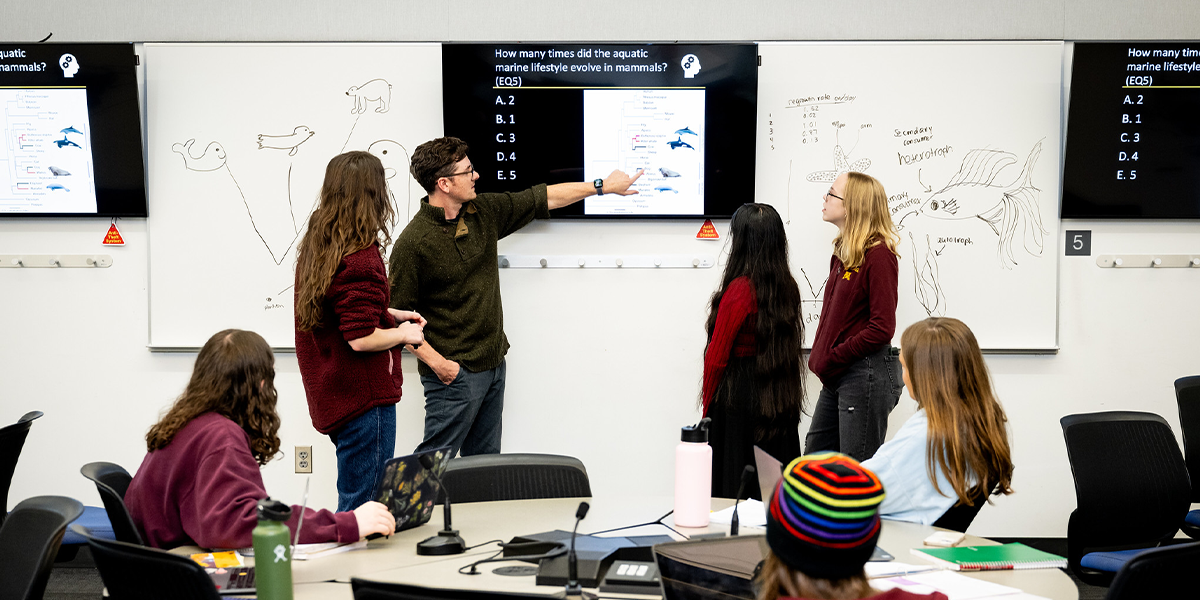

BTL Teaching Associate Professor Charlie Willis with students in an active-learning classroom in Bruininks Hall.

How do students best learn biology? What teaching techniques yield results and, just as important, why are they effective? What does an evidence-based approach to teaching biology look like? Those are some of the questions underpinning the creation of the Department of Biology Teaching and Learning (BTL). Now, as the first-of-its-kind department marks a milestone, those questions continue to drive inquiry in new directions.

“BTL brings together scholars with a deep background in biology and a strong commitment to evidence-based approaches to teaching,” says College of Biological Sciences (CBS) Dean Saara DeWalt. “The fact that we have a department dedicated to discipline-based education innovation sets this college apart and reflects our longstanding commitment to delivering the best possible experience for our students.”

A record of innovation

The department owes its existence to a confluence of factors, not least that it is situated within one of the only colleges dedicated to the biological sciences. Biology education has always been a cornerstone of the College’s mission going back to the creation of the General Biology Program in the 1960s, which was created by faculty to ensure students learned core biology concepts. The College began admitting first-year students in 1997 and soon after then-Dean Robert Elde and colleagues established the Nature of Life program, to introduce students to the College and to each other far away from the distractions of campus at Itasca Biological Station.

In the early 2000s, a major paradigm shift occurred with the start of the two-course introductory biology sequence called Foundations of Biology. The College was an early adopter of active learning, which asks students to work together to analyze data and apply what they are learning rather than spend class time listening to lectures. The first active-learning classroom on campus, designed to support this more interactive approach, was located in the basement of the Biological Sciences Center. Now, there’s an entire building on the East Bank campus – Bruininks Hall – filled with active-learning classrooms. This move toward active learning mirrored a move within the discipline-based education and research field.

“About 20 years ago, a push began across the country to do more scientific analysis of educational outcomes to ensure our students actually learn what we want them to learn,” says David Kirkpatrick, head of BTL. “What we saw across the board was how effective active learning was in the classroom. Leadership within the College saw an opportunity to do something truly innovative with the introduction of Foundations of Biology and, eventually, the formation of a department dedicated to evidence-based biology education.”

Active learning stood the test of time and has proven the gold standard for biology education. “A meta-analysis published in 2014 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences just as BTL was getting off the ground demonstrated that by changing the way you presented your material, not changing the content at all, just the way you presented it you could improve student outcomes,” says Kirkpatrick. Co-author of the paper, Sarah Eddy, is now an associate professor in the department. “From the start, we were asking ‘why does this work?’”

A strong foundation

Foundations of Biology, in particular, presented the nascent department with a unique opportunity to apply findings in real time. “We use our classrooms as laboratories to try things we think work and gather data to make that case,” says Deena Wassenberg, a teaching professor and associate department head. “Being part of BTL makes it much easier to collaborate with people who share a common interest in advancing this work. It creates a feedback loop between research and actual teaching.”

For example, BTL researchers conducted studies that looked at the cadence and content of assessments. The findings spurred changes to how they test students.

In the latter case, the findings were put into practice. “We added new formative assessments instead of just a midterm and final, to make sure that there's progress being made,” says Kirkpatrick, who notes that formative assessments allow instructors to change what they are doing midstream if it’s clear students are struggling with a particular concept or section of the course. “This approach allows a better understanding of how the classes are progressing, and it also reduces student stress levels because the whole grade isn't based just on two grades.”

Throwing out the recipe

Student-driven inquiry extends to the teaching lab as well. In 2019, CBS opened the Dr. Denneth Dvergsten Active Learning Lab — another first of its kind at the University of Minnesota – with an eye to providing students in the teaching lab associated with Foundations of Biology with everything they need to develop and carry out their own experiments without using step-by-step instructions.

“We want them to think through how you actually form hypotheses and do experiments,” Kirkpatrick says. “From there, we want them to work through how you translate those questions into experiments. It really mirrors what's going on in the outside world with respect to biology research, whether that be at a university or a biotech company.”

Making the math work

The Foundations of Biology course sequence is just one avenue for investigating the dynamics that play a role in student success. Anita Schuchardt, associate professor in BTL, is looking at how students make sense of the mathematical equations they encounter in their biology courses. This is a critical issue since mathematical models are an important tool for scientists, but often biology students find it challenging to apply mathematics or lack experience using it in this way. Schuchardt finds that the kind of activity students are asked to do, how instructors talk to students as they work, and group work all influence outcomes when teaching math in a biology context.

“Students who fail to make connections between mathematical equations and biological concepts struggle to solve problems that are not the same as covered in the classroom, therefore, as instructors, we need to help students make connections between mathematics and biology,” says Schuchardt. “If we can help them realize they can use both their knowledge of biology and basic algebra to understand and make sense of these equations, we can change how they view mathematics in biology.” The result: students who are able to better express ideas and solve problems using biology.

All-in on inclusion

Fostering a sense of belonging among students is a top priority for the department. It’s a research focus for many BTL faculty members including Sarah Eddy, a recent tenured faculty recruit to the department. “We are finding that how an instructor appeals to students' personal values through the relevance of content to their lives and future careers is one of the strongest predictors of engagement,” says Eddy.

Former and current faculty members have looked at the role of identity in shaping perceptions of active learning, rethought the curriculum related to sex and gender, and examined differences in performance between genders based on type of assessment.

BTL faculty and instructors are heavily represented in the College’s Inclusive Excellence in Undergraduate Education. Schuchardt serves as faculty mentor for the program, which provides an opportunity for faculty to grow their expertise in inclusive teaching practice culminating in a project on a related topic. Last year’s cohort included five BTL faculty, who investigated early indicators that would allow for targeted intervention aimed at improving student success and reducing any associated opportunity gaps, ways to improve teaching assistant training, and more.

An eye on graduate education

BTL already plays an important role in mentoring graduate students who work in classrooms and labs for courses run by the department. A new $1 million National Science Foundation grant will allow BTL researchers to take a closer look at how graduate program recruitment and faculty-match placement impact student outcomes.

Kelly Lane, an assistant professor in the department, Schuchardt, and postdoctoral researcher Ariel Steele will assess different ways science graduate students are paired with a faculty advisor and how this process may impact student success, sense of belonging, intent to persist in their programs, and satisfaction with their advisors.

“There are pros and cons to the different ways programs recruit and bring in students, but there isn't a ton of research out there that really assesses them,” says Lane. “We want to ask big questions in this space like ‘What is the role of graduate education?’, ‘What are our learning objectives for a graduate student?’, and ‘Why do we do the things we do?’”

U-wide reach

Teaching CBS students is only part of the picture. BTL faculty and instructors also teach courses for non-majors every year. The department teaches nearly 4,000 non-majors each year in several courses such as Evolution and Biology of Sex and Environmental Biology: Science and Solutions.

“One of the major impacts we have as a college is through the educational experiences we provide for thousands of undergraduates each year,” says Tamar Resnick, BTL teaching associate professor and the College’s assessment and curriculum liaison, and a proponent of scholarly teaching.

Students in non-majors courses require a different approach since they typically have less background in biology and their science identity and science confidence are less solid. Making biology accessible, relevant, and interesting while also integrating active learning requires a measure of creativity and intentionality.

“The work we do with our students is important for a number of reasons,” says Resnick. “It helps them develop the tools and ingenuity they need to advance science. It cultivates critical thinking skills they will apply within the sciences and beyond. It also shapes their relationships with scientific data, the scientific community, and their own scientific identities.”

Full-speed ahead

As the department embarks on its next decade, the focus remains firmly on identifying factors that impact student success and improving biology education for students in the College, at the University of Minnesota, and beyond.

With that in mind, BTL continues to learn as much as possible from its first 10 years as well as to build collaborations and share best practices across the College.

Kirkpatrick also underscores the need to study not only what works but also why it works. “Once you understand why something works you can build on it,” he says. “Over the last 10 years, we've looked at specific aspects of active learning such as how students learn quantitative aspects modeling and equations. We plan to continue to drill down to understand those dynamics, apply what we learn, and share those findings broadly.” –Stephanie Xenos

Lance Janssen contributed to this article.