Before Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve became a magnet for scientists from around the world for its longterm biodiversity experiments, it was a humble research outpost where a graduate student named Raymond Lindeman collected data at Cedar Bog Lake. Those long days of fieldwork in 1936 led to insights that would eventually upend conventional wisdom about how ecosystems work.

Up until then, ecologists focused on classification and characteristics of plant and animal species. Lindeman shifted the focus to ecosystems by showing how organisms depend on each other and their environment for survival. His thesis laid out a radical new theory about how energy and nutrients move through ecosystems, beginning with photosynthesis and traveling up the food chain.

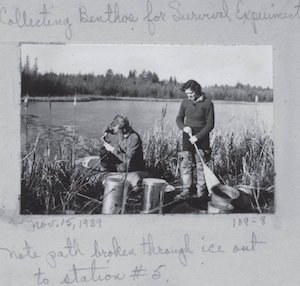

Lindeman contracted a rare liver disease in 1937, but he continued his work with assistance from his wife, Eleanor Hall Lindeman, who eventually became his research partner. Lindeman went on to Yale where he submitted his paradigm-shifting paper to the journal Ecology in the fall of 1941. It was rejected. Lindeman’s illness returned and he was hospitalized for a period, but he still managed to revise the paper and resubmit it later that year. He died the next year at the age of 27.

“Lindeman’s work was fundamental in that he really was the first ecologist to quantify the movement of matter and energy through an ecosystem,” says Jim Cotner, a professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior. “Lindeman recognized that all of the organisms in an ecological setting were connected to each other energetically — all the way from microbes up to the top predators. And he recognized that it is the movement of matter and energy that actually makes an ecosystem an ecosystem. His work in tiny Cedar Bog Lake set the stage for many of the ecosystemscale studies that are done at Cedar Creek and all over the world today. It also laid the groundwork for understanding of the whole Earth as an ecosystem, what we now refer to as global ecology.”

Cotner recently received funding from the National Science Foundation to bring Lindeman’s work in Cedar Bog Lake into the 21st century by quantifying the exchange of carbon dioxide and methane, another important greenhouse gas, with the atmosphere. “Similar to combustion of fossil fuels, organisms in all ecosystems produce these gases as end products,” says Cotner. “The work we are doing will help us understand whether and when lakes are important as both a source and sink of these gases.”

Today, visitors to Cedar Creek are likely to spend time in the Raymond Lindeman Research and Discovery Center a short distance from Cedar Bog Lake. The lake remains a landmark and a source of inspiration for scientists all over the world, including College of Biological Sciences ecologist Jeannine Cavender-Bares, who launched one of the newer long-term experiments at Cedar Creek to investigate forests and biodiversity.

“The sheer beauty of Cedar Bog Lake makes it special,” says Cavender-Bares. “You pass through several different ecosystems to get to it. You go through an upland knoll, you go through a cedar wetland area, you go through alders that are fixing nitrogen. Then you get to the lake, and you can imagine Raymond Lindeman doing his experiments, really having this tremendous vision of the flow of energy and materials through that whole system. He thought very holistically in a way that people hadn’t done before at the system level. Visiting here is a very powerful and inspiring experience.”

A Microcosm of Minnesota

Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve is a living laboratory just an hour north of the Twin Cities. No place as close to the metro area can match its biodiversity. Minnesota’s habitats all find a home here spread out across nearly nine square miles in East Bethel, Minnesota. This renowned long-term ecological research station has produced some of the most important insights about biodiversity and ecosystem ecology of our time. But experiencing the diverse landscape is a challenge for visitors, especially those with limited time or mobility. The Minnesota Ecology Walk could change that. The wheelchair-accessible path will take visitors through each of the environmental biomes present at Cedar Creek, with lessons about biodiversity, ecosystems and more along the way.